The Examined Life Conference is a gathering for the medical humanities hosted by The University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine. The conference is focused mainly on the intersection of writing and medicine, and is cross-pollinated with the literary chops of organizations like The Iowa Writers’ Workshop and The Iowa Review.

Dr. David Thoele, the Director of Narrative Medicine at Advocate Children’s Hospital, has been going for years. He introduced me to the conference, and convinced me to submit a workshop.

Now that the conference is behind us, here are some thoughts as I reflect on what I took away:

The First Day

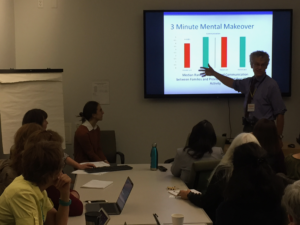

Early in the day, I reconnected with Dr. Thoele and two members of Advocate’s Narrative Medicine Committee, Dr. Danielle Baran and Jemi Gunalp. They presented their clinical research on “The 3-Minute Mental Makeover”. I knew about “3MMM” from my time with the committee, and was encouraged to hear the findings. One of the biggest barriers people have to using writing exercises in clinical practice is the time commitment. We know journaling is medically therapeutic, and Dr. Thoele became frustrated that no one seemed to want to spend time doing it. He finally trimmed down some of his favorite writing prompts into a 180-second exercise. After perfecting it, he and some other researchers at Advocate are now collecting clinical data on how it helps patients’ stress levels.

There were some other wonderful cultural experiences from the day, such as hearing Ghada Al-Absy, an author and doctor (and Cairo Opera House soloist!) read from her work. The crowd listening to her readings also managed to persuade her to sing some selections from her previous opera performances.

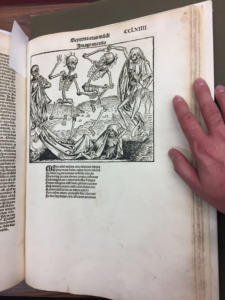

The John Martin Rare Book Room at The University of Iowa is currently exhibiting works about the Black Death. I’m thrilled that I can now say I’ve touched a copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle.

The talk I’ve chewed on the most since leaving the conference was presented by Dr. Courtney Bruntz, Dr. Heather Lambert, and Philip Weitl of Doane University. The presentation started with Mr. Weitl talking about his creative writing classes, and his growing concern that his students were ill-prepared to use traumatic experiences as subject material.

Dr. Bruntz, who is an expert in Buddhist Studies, then gave a brief description of the Buddhist view of the Self, which is quite different from the Western, Christian view. Dr. Bruntz used that as a primary example of her undergraduates’ experiences confronting viewpoints in the world radically different from their own. In particular, she talked about our view of our own Self, and what happens to the view US undergraduates have of their Selves when the world fails to meet their expectations and they fail to meet their own ambitions.

Then Dr. Lambert, a clinical psychologist, used that tension between our expectations and reality as a launching point. She discussed various studies which indicate that far more people are walking around in the world with personal trauma than we imagine. She also added her own experiences going from the practice of clinical psychology with violent, incarcerated offenders to the practice of psychology with Nebraska college students. She assumed she would be dealing with homesick students, stressed by organic chemistry. She found that a wide cross-section of students is dealing with genuine, clinical trauma.

Mr. Weitl then wrapped up by saying that his students brought their trauma — issues like the suicide of a parent, sexual abuse, drug addictions — into his writing class, and asked the big question: what do we do when students want to write about them? Working out these experiences through writing can be therapeutic, but it can also cause the victim to relive them.

The answer Mr. Weitl came to is relatively straightforward: “You don’t have to write about everything.”

He went back to the structural underpinnings of writing (near to my heart), and talked briefly about what I have always called the “Superobjective”: a profound awareness of a lack of something. His point in talking about the theory behind storytelling was to go back to the idea of character. If you can pinpoint what the character wants in the long term, you can show how trauma changes the character. As an example of this, Mr. Weitl brought out a Vietnam War memoir, In Pharaoh’s Army, by Tobias Wolff. There’s very little of the Vietnam War in this war memoir. Instead, Mr. Weitl pointed out that the book’s main character responded very, very differently to identical situations before and after the war itself.

The Second Day

The second day of The Examined Life Conference featured Mike Scalise, an author and journalist who had his own health scare. His new book, The Brand New Catastrophe, not only tells that story, but it also identifies tropes of the illness memoir (probably of all memoirs), and he fits different parts of what happened to him into those different tropes: difficulties with a father figure, the noncompliant patient, etc. He also talked about his preferred use of humor. The selection and arrangement of different things that happened to him, he said, can point out just how absurdly funny it can be to have an illness and seek treatment.

My alma mater was represented, too: Dr. Ernie Esquivel, who teaches Clinical Medicine at Weill Cornell was there, and read some reflective pieces that his students wrote. We think of med students as just beginning in their ability to process the disease, the pain, and the death that they see around them. The reflections Dr. Esquivel read were extremely well-developed and heartfelt. He put the reflections into several different categories, and talked about his student’s encounters with each one of the different aspects of being a physician learning to practice.

The keynote speaker of the conference was Dr. Rafael Campo, who spoke to a packed house about his experience being a general practitioner, a poet, and a medical educator. “When I decided I wanted to become a physician,” he said, “I didn’t have many Latino role models. I thought that might be an issue. I’m gay, and I thought that might be an issue. I never imagined that the biggest issue would be being a poet.”

My own presentation, given on the last day of the conference, tries to answer the question, “What are stories good for in the physician-patient encounter?” When we talk about “Narrative Medicine”, we often talk about our ability to process stories completely separate from the face-to-face encounter of a healer and a sick person. One audience member asked Dr. Campo about this, “Once you’ve written a poem about a patient, then what? Do you read poems with your patients? Do you prescribe them?” Dr. Campo joked, “Well… I certainly never prescribe my own poems to read.” While the room laughed, I admit I was a little relieved that someone else was wondering about what I came to speak on: What are stories good for in the moment?

The Third Day

At long last, the big day arrived. I titled my workshop, “Moving from Stories about Practice to Practicing with Stories”. I briefly told my own story with chronic illness, and why it’s important to me to focus on medical storytelling. I went over the basic structure of a story, why it’s effective, and some ways that it might be used inside a medical practice. Then, I opened up the floor to see if anyone wanted to take a shot at telling their own medical story.

I was thrilled with the discussion. The first person to try out their story on the group was a woman who — like me — suffers from a chronic illness, and who has been trying to find a way to talk to her doctor about adjusting her medications. We rooted around for a little while, and tried to find the root problem (the beginning of every story), and based on her feedback, I think she found a new way to discuss with her doctor what is working and what isn’t about her treatment.

Next, a psychiatrist asked about a patient of hers who has been asking to go back onto a particular medication even though it’s presented extreme side effects. The young woman is apparently insistent that she take a certain drug to help her focus in school, even though on the drug she’s experienced severe weight loss. As a group, we discussed several different flows for a potential story the psychiatrist could work on with the young woman.

The last person who wanted to share a potential story with the group was a midwife. She’s trying to find ways to tell her patients that the pain they experience from the time they go into labor until they receive pain treatment at a hospital, etc., is likely going to be more severe than they think it is.

I enjoyed the workshop and getting to share my work. I also enjoyed a few reminders about what doing this work is like:

The first: finding the root problem which a story expresses always takes the most time. Once there’s a visceral, palpable problem that can be expressed, the story proceeds from there. With each person who spoke, we spent the most time discussing how to articulate the problem (that is, how to begin the story). That’s normal and natural, and I’d almost forgotten how much fun it is.

The second is that sometimes, people reject your story. I had been stressing about having something meaningful to say during this conference. The days ahead of my own workshop had been spent keeping an ear to the ground to see if the kinds of things I was going to be talking about were things people would find useful. When the psychiatrist mentioned that she was seeing a patient who was begging to give up her own well-being for the sake of her grades, we talked about how to articulate the problem. The psychiatrist had articulated all of these in various ways at one time or another. In my effort to be useful to the people around me, I had forgotten: if someone doesn’t agree that the problem you articulate is a problem, which will happen from time to time, they aren’t going to hear the story you have to tell.

The last story, trying to articulate how bad labor pains are going to be before you reach the hospital, is an interesting one, and I think it’s one that I’ll have to chew on. In the workshop itself, we came up with several good drafts of a story to tell mothers- and fathers-to-be. I know the midwife took home some new ways to think about talking to her patients. I don’t know, though, if we found a story that was the most effective it could be. It’s a wonderful question: how do you make someone understand a story whose events they’ve never experienced before? How do you prepare someone for something when they have no frame of reference?

After my own workshop, two others closed out the conference: Dr. Leslie C. Morris, a Professor of German Literature at the University of Minnesota, read from her own medical memoir. The timing of her illness coincided with the discovery that her mother had deliberately hidden the fact that they had relatives who died in the Holocaust. The upcoming book and multimedia project, She Did Not Speak, contains a wonderful parallel account of a family story moving from Old to New World, and a personal account moving from sickness to health. The author mentioned that some doctors even thought her illness was brought on by the trauma of discovering a family secret, even if the author herself doesn’t believe that to be the case.

To close out the conference, I heard Amy Lintner and Alex Waad speak about their work on medical education and transpersonal psychology. Their discussion of the idea of empathy as an object for study was refreshing. It was a theme that some conference speakers had touched on, but were never able to make concrete. It’s clear a lot of research, study, and fieldwork went into their work, and that the ideas they covered in their presentation were clearly only the tip of the iceberg.

The discussion during the session drifted from their research onto a question which was apparently on one woman’s mind: why should a medical professional ever introduce themselves and introduce their preferred pronouns (she/her/hers; he/him/his; they/them/their; etc.)? I have to give the speakers credit: they didn’t mind the bunny trail. People in the audience felt very strongly about the issue, and the speakers treated everyone with a genuine respect and gave everyone their full attention while they were facilitating that discussion. In the same context, I don’t know that I’d be so gracious as to have a conversation completely tangential from the small mountain of research I had prepared.