Mechanical and Mutual Exchanges

I was originally introduced to Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay “Telling is Listening” through Maria Popova’s Brain Pickings. She has a terrific discussion of Le Guin’s metaphors about communication as we think it is vs. how communication really works.

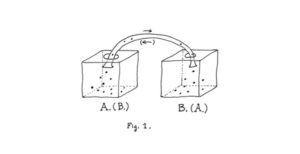

Le Guin uses the “machine model” to illustrate how we sometimes think we communicate: one entity exchanging quanta of information with another entity. Giver, message, medium, receiver:

She admits that sometimes, communication does work this way, especially regarding brief, actionable items. Usually, though, our communication is more than just information. Normally, communication means that information, the medium of our communication, and the speakers themselves are all embedded in a culture. Le Guin separates information from meaning, and meaning, she says, is enormously complex and utterly contingent

.

True communication is not a stimulus to be decoded, but a mutual exchange which affects both the teller and the listener. Le Guin uses the example of the sexual exchange of DNA between two amoebas. Each literally gives a piece of itself to the other.

Literate and Oral Cultures

All this I remembered from reading Popova’s article. What I didn’t remember was how Le Guin dives into the differences between a literate culture and an oral culture, and how that difference affects our communication.

Part of the point I tried to make at the recent Examined Life Conference was that oral speech predates literacy and writing. Writing about medicine and our medical experiences is profoundly useful. If we don’t consider, though, how we can express our humanity orally — when a healthcare provider and a patient meet face to face — we’re not considering the whole picture of how narratives can help heal.

Le Guin often quotes Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy, and uses his discussion of an oral culture vs. a literate one. One is not necessarily better than the other, but they do produce different social dynamics.

The big advantage of a literate culture is that writing produces a cultural artifact. It is reproducible. Knowledge and information can be handed down more easily. The advantage of an oral culture is that listening to someone speak is the easiest way to create a relationship. A book can sit on a shelf untouched for a generation but a crowd listening to a speaker is connected.

Le Guin has a brilliant passage about seeing, hearing, and Mount St. Helens. She can look out her window and see Mount St. Helens every day. Only one day in 1980 could people hear Mount St. Helens. Seeing confirms existence, but hearing is an event.

This distinction between reading and hearing sounds quaint, but it is literal and physical. Le Guin cites the work of William Condon, who found that when an audience is listening, they actually move their mouths and bodies in very subtle ways that mimic the speaker. Listening in the presence of a speaker is to participate in the speech. Speaking in the presence of an audience changes how the speech is delivered, since what we have to say is shaped… by actual or anticipated response

. Being physically present with a speaker is to be in proximity to their body, which is moving the air around the listeners. According to Condon, live, face-to-face communication is shared movement

.

Le Guin also discusses Ong’s idea of “secondary orality”, which is the fact that after the ability to write ideas down, human beings developed the ability to record oral speech. What we call “media” can’t create a relationship between speaker and listener in the way that “primary orality” can. Media and recordings can move people, of course, but the communities created by secondary orality are usually mental ones, and don’t have the advantages of bodily participation. We can view a reproduced image of a speech, etc., but the original event — the one ultimately co-created by speaker and listener — is gone.

What Any Of This Has To Do With Medicine

In an oral culture, Le Guin writes, oral performance takes on a formality. Oral performance creates its own “space”, which has very little to do with physical space, but an area where people are connected by hearing. There is something of that formality left in great political orators, seeing actors perform, Presidential Inaugurations, or hearing a poet speak their work aloud. Granted, we often have the text of these ahead of time. There are still occasions in our literate world, though, when the speech act is elevated beyond something that we could just read the next day. There are still times when the experience of hearing creates community.

There is something of that oral formality left in a doctor’s visit.

The speech of a physician is important. The ability of a doctor to listen and to talk is a part of healing. People want someone — a professional — to take care of them in their illness. If “Telling is Listening”, then the patient is changed as they tell about their symptoms, the physician is changed as they tell about a likely diagnosis, and both are changed as they communicate reciprocally in the exam room.

Writing and literacy are still important parts of medicine. We create written records of symptoms, diagnoses, test results, and medications so we can reproduce them easily.

That doesn’t change the importance of talking with a physican about medical history, the consequences of an illness, and medication usage. That doesn’t change the central importance of a physician’s ability to communicate face-to-face to a patient.

Sources

Guin, Ursula K. Le. The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. Boston: Shambhala, 2004.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Methuen, 1982.

Condon, William S., and William D. Ogston. “Speech and Body Motion Synchrony of the Speaker-Hearer.” In The Perception of Language, 150–84, 1971.